By Bart Magee, Ph.D. There’s no debate that the prevention of COVID-19 in the U.S. has been a complete failure. After some initial success in April, the current situation in much of the country is like an uncontained wildfire. Years from now, books will be written about the multitude of mistakes, but we can’t afford to wait as the deaths pile up. There is still time to for us to switch to proven prevention strategies. The main shortcoming from a mental health perspective has been how anti-psychological prevention efforts have been. Public health strategy depends on changing basic human behavior – how people interact socially makes the difference between infection and containment. Human social behavior is complex and is driven by a multitude of needs, attitudes, habits, and emotions. Little of the COVID-19 public heath messaging takes this into account. Most of it focuses solely on getting people to isolate which can only work in the short term. The narrative of “shutdown” and “reopen” sets the stage for the current disaster by giving people the false impression that we just stay inside until it’s 100% safe to go “back to normal”. I wrote about this problem in March, and the current rise in cases bears that out.

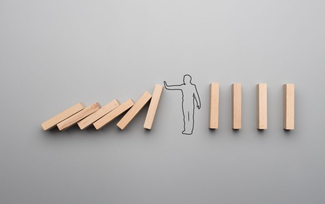

Mental health problems related to living in a constant state of fear and isolation have increased, yet fundamental social behaviors have yet to change sufficiently to stem the spread. Public health officials are increasingly frustrated and seem clueless about what else to do. They wring their hands about people going to house parties, yell louder about mask-wearing and obsess about which businesses should be open and which should be closed. The messages are often confusing, don’t target the people most at risk, and don’t support the fundamental need that people have to connect to one another. What if we tried something different? How about an approach that considers psychology and all the knowledge we have about human social behavior? We have only to look to the recent past, right here in San Francisco, and the successful efforts to tame the outbreak of HIV/AIDS among gay men. I remember that time and believe that I’m alive today due to the work that was done by a creative collaboration among social scientists, public health experts, and community activists. During the early 1980s, a terror that gripped the City as a horrifying and deadly disease afflicted gay men. I remember the first time I heard from a friend about this strange “gay cancer.” I remember calling my father and telling him the story. I cried to him on the phone, not knowing if I’d be next. It was quickly understood that a virus was destroying the immune systems of these men, leaving them vulnerable to opportunistic infections like Kaposi Sarcoma and Pneumocystis. It wasn’t long before health experts identified a sexually transmitted virus as the cause and researchers at UCSF led the way in understanding it and how infections could be prevented. Anal sex was determined as the primary cause of transmission and condoms were then recommended for intercourse. Like today, hysteria, misinformation, conspiracy theories, and denial all spread throughout society. There were also raging debates regarding the balance between civil liberties and public health, debates that culminated in the decision by San Francisco to close the gay bathhouses in 1984, one that ultimately ended up in court. At that time, we gay men didn’t trust authorities, and for good reason. The police had only recently stopped raiding gay bars. The murder of Harvey Milk (by a former cop) was still fresh. We held massive vigils on the anniversary every year. Ronald Reagan, the President, ignored the AIDS crisis while close to 100,000 people died on his watch. Given this situation, a top down approach to HIV prevention would never work. In addition, gay men had been and were still fighting for rights and sexuality was core to that fight. Any prevention effort that centered on telling gay men that they had to abstain from sex would be akin to sending men back into the closet they had fought so hard to emerge from. That kind of effort would have failed and resulted in more disease and death. Prevention had to focus on suppressing risky sexual behavior while preserving sexual freedom and healthy sexual relating. One of the innovations that researchers at UCSF created was the Mpowerment Project. The model, that proved initially effective and has since spread around the world, is a bottom up, community-based approach that not only teaches safe, healthy behaviors, but also recognizes that addressing psychological and social issues (anxiety and depression, self-esteem, racism, homophobia) plays a key role in prevention. The project’s greatest innovation was to staff it with peer support volunteers who are mentored by paid staff. Volunteers organize outreach events to bring those at risk together and build a network of support. The psychology of the program is empowerment, which is the foundation on which the prevention efforts are based. Think about that for a moment. Rather than creating an atmosphere of fear, the organizers first developed an environment of community and interpersonal connection. The psychologists who created the program were guided by two important principles, first, that behaviors are interpersonal and powerfully influenced by our friends and peers; and second, that better choices are made not out of fear, but from a place of healthy self-esteem and interpersonal confidence. This approach borrows a page from “harm reduction,” which starts by recognizing that there are always harms associated with behavior, and rather than thinking in terms of absolute risk avoidance, it emphasizes evaluating risks and making healthier personal choices. What would this look like today? First of all, that would mean starting with two basic assumptions: that COVID-19 is here to stay and that people want and need to be around each other. Mental health and human connection go hand in hand. For these and other reasons, it makes little sense from a public health perspective to keep people from gathering. The goal is to teach people to be safe with one another. The blunt, fear-based messaging should be replaced with something more positive, supportive, and harm-reduction focused. For example, since all experts agree that crowded indoor spaces where mask-wearing is difficult are the most dangerous (bars, house parties, churches, etc.) and that outdoor environments are safe, a good public education campaign might be: Safer Outside. That would encourage people to take all gatherings outside, give them creative solutions for doing that, and teach strategies for people to encourage each other to stay safe (i.e. how to speak to a friend when you see them not maintaining physical distance). Otherwise, the campaign would emphasize the health benefits of outdoor activities, exercise, fresh air, socializing, and fun. Second, we should be focusing our efforts on communities hardest hit. In California that means working-class and Latinx communities. Right now in California, 55.6% of new cases are among Latinx people who make up 38.9% of California’s population. It’s well understood that economic realities (greater proportion working in front-line jobs, lower pay, little or no sick leave) and fears (job loss, deportation, and bias) make prevention work more challenging within this community. Devoting more resources and energy to heavily impacted populations would deliver the greatest gains. Similar to what was done in SF in the gay community during the AIDS years, training community-level, Spanish-speaking volunteers to provide information, emotional and financial support, and connection to resources would make a big impact. A similar effort could be made to reach young people, who are making up a larger and larger share of new cases. By taking a more psychological approach to prevention, we can also help to tame the mental health crisis that is currently building across the country. The time is ripe for a mental health education campaign that would teach people basic psychological first aid. Everyone could be taught the basic principles and techniques of psychological resilience: creating psychological safety, managing emotions, maintaining connections to others, establishing self-efficacy and control, and finding hope. These principles are core to recovering from crisis and trauma and not only can they be applied to one’s own life, but can be used to help family and friends who are struggling to cope with the impacts of the pandemic. This would create a positive feedback loop. As people are better able to care for themselves and their loved ones, they would be in a better position to take in and promote public health measures. It’s time to stop paying lip service to “We are all in this together” and start doing the things to give that statement some real meaning

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2024

Categories |