|

By Bart Magee, Ph.D. The recently released documentary film “Won’t You Be My Neighbor” is bringing people together. It’s a rare film that has both critics and audiences raving. (You really can’t beat a 99/98 Rotten Tomatoes score.) And it’s not a big surprise that the film is breaking box office records in the documentary genre. As an auspicious story about an unlikely hero who championed compassion and had an uncanny ability to understand the needs of children to be seen and cared for, it’s a film preordained to warm hearts, open tear ducts, and kindle nostalgic daydreaming. For many, it’s been a welcome antidote to the poisonous and divisive atmosphere that has taken over the national discourse. In my view, the meaning of the film and its potential impact goes much deeper and has real implications for how we think about mental health as well as the well-being of our community. With that in mind, I’d like to explore two of Fred Rogers’ main concerns, the first being the concept of childhood and the second being neighborhood. For Rogers, the two concepts are intertwined. In his distinctively gentle and relaxed manner, Rogers develops his ideas around these concepts with a vision of radical cultural change. Childhood

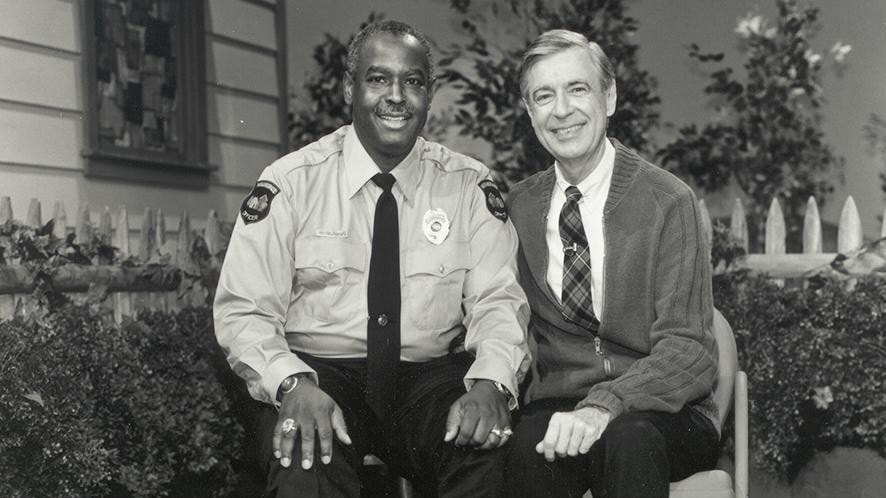

A patient of mine recently said that for him it all comes down to the difference between “childlike” and “childish”. He was addressing something vitally important in his development, but also pointing to something larger. There is a tension in our culture between two different ways of thinking about childhood. In the culturally prevailing notion, childhood is mostly something you grow out of. It’s a kind of untamed territory that must be civilized. There is wonder there, innocence, and fun, but it’s something to be left behind as one grows up. We need to grow out of our childish notions, our neediness and dependency and learn to be independent adults. This conception doesn’t see growing up as particularly enticing and therefore utilizes both the carrot and the stick for motivation. The carrot being the promised rewards of adulthood: you get to be big, make your own choices, and have money/power. The stick is shame. “Grow up!” “Stop crying like a baby!” “Get over it!” The implication is that if independent adulthood is painful or difficult for you then something is wrong with you and you’d better pull it together, otherwise a life of humiliation awaits. Childhood, in this view, is a problem, a kind of necessary evil that must be overcome in order to live a successful, happy adulthood. In the film, Rogers speaks to this when he expresses his dismay at the state of children’s television in the 1960s and how that helped him shape the nature of his show. Children’s TV at the time (and much so today) followed the dominant cultural script. It focused on childhood as the wild and crazy era, as Rogers said, it was all pies in the face and frenetic activity and the advertisements focused on teaching children to become good (adult) consumers. The other problem with this model of development is that it doesn’t provide many tools to help children learn about and navigate growing up. Rogers understood this. Childhood and adulthood can’t be so neatly separated. In the name of protecting children, adults often do them a disservice by not talking to them about the many painful realities of the world. The common refrain heard is, “they are not old enough to handle it.” The “it” being everything from divorce to war, racism, illness, and death. Rogers was passionate about making sure that children were told about all these things in language they could understand, thereby giving them the meanings and tools they need to make sense of the world. Even after his show was off the air, he would come back in moments of national crisis to speak to children. Just as Rogers understood that children are exposed to the realities of the adult world from day one, and it’s the job of adults to help them comprehend those, he also believed that childhood lives on in us as adults. You never really grow out of it. This gets to the radical or countercultural idea about development that Rogers was promoting. Childhood lives on in us forever and because of that we need to attend closely to “childlike” feelings and experiences and recognize them as vital in the process of growing up. Rogers recognized that the various indignities of childhood (being small, having a body and emotions you can’t really control, feeling different, scared or alone) need to be recognized and soothed. Again, his approach was radically different from the one that says, “don’t worry, you are making too much of it,” “it will be ok,” in other words, “you’ll grow out of it.” No, he says, these feelings are real, they are scary and overwhelming, but no matter what you feel, you are loved and you will never be abandoned. That’s the true meaning of the refrain we most associate with Rogers, “you are special just the way you are”. It’s not just about self-esteem, which is how many people hear it. It’s about telling a child that no matter what they feel, no matter what they are worried about there is nothing wrong with them. Children do need that reassurance. This is where his critics really got it wrong. He wasn’t telling children that they are better than others, and turning them into entitled brats. He was emphasizing the definition of the word “special” that means “unique.” You are designed for a specific purpose, you have value, your life has meaning. Right here, Rogers does away with the carrot and the stick. He trusts development. Children don’t need to be incentivized to grow up and they don’t need to be shamed into it either. But they do need help in growing up. They need to be reassured that growing up doesn’t mean abandonment, and that life, whether it’s a child’s life or an adult’s has meaning. And meaning, provided within relationships, is what helps us tolerate all the pain and loss that development entails. Neighborhood This leads us to mental health. Why does our modern society with all its wealth, comfort, and advantage leave so many people suffering with depression, shame, anxiety, self-hatred, and lack of purpose? Why does mental wellness appear to be inversely related to a society’s wealth and “modernity”? Many adults, like the patient I mentioned above, seek therapy because they suffer with childhood feelings. They feel they are bad because they continue to have feelings of dependency or need for recognition. They are confused, have trouble handling their emotions and can’t seem to “pull it together”. While the stigma has lessened, many people still feel like seeking help from a therapist is a sign of failure. In short, they took in the messages from the culture, mediated by their parents and families, that childhood is somehow shameful and needs to be left behind. Much of what therapists engage in is undoing this notion and allowing space for those disavowed feelings and experiences, and like Fred Rogers, trusting that with recognition and support, development will take its course. So how does Mr. Rogers “neighborhood” fit in? Again, Roger’s is working to upend a foundational conception of how we organize ourselves socially. Traditionally in our culture there is an emphasis on two structures of social organization, the family and society. We are the member of a family and the citizen of a nation. In the family we are a son, daughter, cousin, father, mother, etc. In society we are a student, employee, customer, professional, soldier, constituent, etc. The family is a place of intimacy and history while the social sphere is one of public transaction and future potential. And like some of the traditional notions of childhood and adulthood, the two realms of social interaction are vastly different. In his concept of a neighborhood Rogers is trying to bring the two together. “Won’t you be my neighbor” is both an intimate (family) request, and a public statement. You are a stranger, you are outside my family, you are part of that larger social group and I want you to be my neighbor. Though you are far, I want you to be near. With neighbor and neighborhood, Rogers recognizes the need for a social group and relationships that bridge the gulf between family and society. That gap is too big, he implies, and children need a social stepping stone to cross it. Rogers organizes his television show around a fictional neighborhood, giving children that safe and intimate place to step out into the world, where they can try out different roles, find models, address conflicts and nurture social relationships. The neighborhood is also the place where children can learn about and cope with some of the more painful aspects of the world. In the neighborhood the child encounters differences and social problems, like poverty and racism, in a way that is experience near and comprehensible. Rogers models this over and over again in the show. In one moving scene, he addresses the racial strife of the 1960’s, specifically the segregation of public swimming pools, by washing his feet in a kiddie pool with François Clemmons the neighborhood’s black police officer. In another, he employs Daniel, his puppet alter ego, and an inflating and deflating balloon to address life, death and the assignation of Robert Kennedy. Big subjects for a little neighborhood. Access Institute’s Neighborhood With everything going on in the world today, we need the neighborhood more than ever. Where do we find it? And how can we, the Access Institute community, create a neighborhood here in the Bay Area that nurtures, fosters meaningful relationships and forms that bridge from family to society, through childhood and adulthood that Fred Rogers would recognize? I see our neighborhood taking many forms. Access Institute’s many partnerships are based on a neighborhood model. For example, our in-school mental health program treats each school as having a neighborhood role. School is not just a place where we educate children and prepare them for adulthood. It’s a place where recognizing the significance of their experiences happens in real time. We help the schools respond to children’s emotional needs in the classroom, in the hallways, and on the school yard. We help make something of those experiences. And we do that by becoming part of the fabric of the school. The therapy relationship is just one piece. We facilitate all the relationships whether that’s with a teacher or a volunteer mentor and we also mind the child’s relationship to the school community in which she can express her unique potential. This, we believe, helps to form that bridge to the future that every child needs to thrive. And it’s not just in childhood that the neighborhood matters, it’s at the other end of the lifespan, too. As older adults experience the multiple losses that accumulate with age, they need more than solid family relationships and adequate medical care, they need the holding and mutual recognition found in a neighborhood community. In our partnerships with senior service organizations (Bayview ADHC and Openhouse) we also foster multiple forms of intimate and public relating. These relationships help to buffer the losses inherent in getting older. In these settings our therapists move between the private individual sessions, to facilitating group process among the seniors to interacting with staff and seniors in various milieu settings. Our therapists have specialized roles and they are part of the neighborhood. The neighborhood is fundamental to our values. The first one we enumerate speaks to it: Fostering a community of caring and mutual responsibility. At all levels of our organization, we take that to heart, that none of us are alone and each of us thrive in a neighborhood where everyone looks out for one another. Fred Rogers also inspires us to take those values and promote them in our community. I can tell you that Access Institute is focused on this and we know there is so much work to be done. Right now, we are developing new partnerships and programs based on those values and thinking strategically about multiple avenues to foster a neighborhood community here in the Bay Area, one where we truly care for one another and recognize each person’s unique contribution to the greater whole. A neighborhood where Fred Rogers would find himself at home. To learn more about Access Institute and the services we provide, please visit our services page.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2024

Categories |